The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there. The deep past is so weird and wonderful it's practically another planet. I've enjoyed the sheer otherness of artists' attempts to recreate scenes from deep time since I was a kid. Here's an illustration of "early forms of life" from the pages of the Odhams Encyclopaedia for Children I was given for my 6th birthday. The artist was one John Rignall:

It's the sort of busy scene, packed with weird and wonderful detail which might appeal to a child, and it did. Looked at from a half century later it shows how far and fast reconstructions of the Mesozoic world have changed. From the kangaroo-posed therapod to the offended-looking tail-dragging sauropod to the absence of feathery dinos that aren't Archaeopteryx, the ancient creatures all have a retro look.

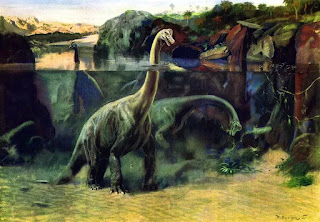

OK, it's an impressionistic overview for kids, including an assemblage of plants and animals most of which lived many millions of years apart from one another. But even the more "realistic" dino books I had as a kid featured reconstructions like this one by Zdenek Burian, of semi-aquatic Brachiosauruses adopting a watery lifestyle to take the enormous weight off their feet:

Some people are, apparently, a bit fed up that the dinosaurs they thought they knew as kids have been superseded by new best guesses at what these creatures looked like in life. Personally, I find a lot of the new paleoart keeps the sense of wonder I had as a child new and fresh.

For a taste of what I mean, I can warmly recommend a visit to Dr Mark Witton's wonderful paleoart-themed blog. It's full to the brim with strange, beautiful and astonishing visions of past life by Mark and many others. From my personal favourite for their sheer weirdness, the giant azhdarchid pterosaurs, to bizarre big-headed predators from the Triassic, or Diplodocus, there are wonders on every page. And also discussions of why (scientists think) these critters look the way they're illustrated.

There is, for example, an interesting post on lips versus exposed teeth in illustrations of extinct carnivores. That post seemed, at least to this non-expert, to make a pretty solid case for assuming lips in all but a very few cases. Interestingly, John Rignall's therapod dinosaur from my childhood encyclopaedia, although its teeth are showing slightly, looks as if it has lips. At the very least, Rignall has made it ambiguous and not as boldly and ostentatiously toothy as many lipless carnivorous dinosaur illustrations of the time:

Also interesting that, from all the big, fierce , famous, carnivorous dinosaurs he could have chosen, (T Rex, Allosaurus, Megalodon), Rignall chose the obscure Antrodemus, a contested name for what most paleontologists would call bits of an Allosaurus. Although Rignall might be up there with modern paleoart with what seems to be lips on his Antrodemus/Allosaurus, the kangeroo posture and palms-down hands is definitely retro dino - compare and contrast with this modern reconstruction of the posture of Allosaurus jimmadseni:

|

| Image credit: Scott Hartman (Creative Commons Attribution) |

The other great thing about Mark is that, although there's lots of solid science in there, he doesn't take himself too seriously and he's generous with the playful pop culture references; see What Daleks, xenomorphs and slasher movies tell us about palaeoart and here, on his Twitter feed, Mark imagines what a gorilla the size of King Kong might actually look like, (given the biomechanics of very large animals, not much like a gorilla):

|

| "It was skeletal and circulatory weakness killed the beast. We've come up with a patch for these issues with the release of Kong 2.0." |

This is fantastic (in both senses of the word), but it's worth remembering that scientist's current understading of the constraints on the size and shape of animals is built on some old and well-established principles. As Stephen Jay Gould once noted:

Galileo first recognized this principle in his "Discorsi" of 1638, the masterpiece he wrote while under house arrest by the Inquisition. He argued that the bone of a large animal must thicken disproportionately to provide the same relative strength as the slender bone of a small creature.For more speculation on the biology of oversized apes (in this case of the human variety), this video on the biology of giants by YouTuber Trey the Explainer also has some fun with the topic of biological scale:

I'm liking this stuff very much. Almost as much as this awesome poster for the, sadly unmade, Hammer movie Zeppelins v Pterodactyls. Yes, I know I've shared this image before but honestly, just look at this thing. As Dr Johnson almost said, when a man is tired of pterodactyl-on-Zeppelin action, he is tired of life.

0 comments:

Post a Comment